Jan Krč

I was born on September 12, 1956, in Prague. I have fond memories of my childhood here. We lived in Vinohrady on Budečská Street, and my younger brother and I went to elementary school on Sázavská Street, where I finished the fourth grade in June 1967. Immediately during the following summer, we escaped to Austria. I mainly remember Sokol Hall in Vinohrady, where we went swimming, and skating in Grébovka park. There was no subway at that time, but I liked to take the tram to visit my grandfather on Petřiny, where he had a beautiful garden with fruit trees. Unfortunately, his health had deteriorated from five years in a communist camp and he died before we escaped, he was only 57 years old.

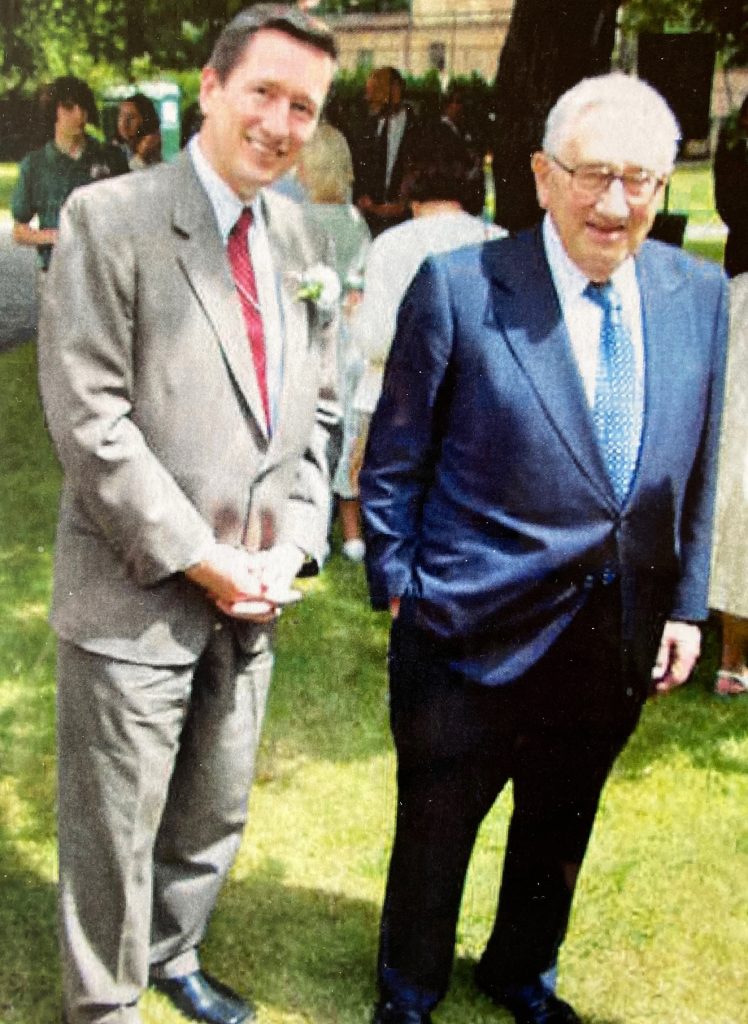

He met us in Austria, and later picked us up at the airport when we landed in New York in late September 1967

My mother’s cousin was the anthropologist, Leopold Pospíšil, known for his research on the tribes in Papua-New Guinea, among the Inuit and Tyrolean highlanders. He emigrated to the USA in 1948. When the communists found out that my mother was corresponding with him, they fired her from the medical laboratory assistant position at the Military Hospital. My father had a good cadre profile (he came from a family of railway workers), but as a doctor he was invited to join the Communist Party. He categorically refused, which, of course, made his career advancement and the possibility of better accommodation impossible. Hence, we lived with my grandmother in two rooms. I myself met uncle Losík, as we called Pospíšil, personally only after our emigration. He met us in Austria, and later picked us up at the airport when we landed in New York in late September 1967. Thanks to him, we obtained visas and in New Haven where he lived, I also experienced America for the first time.

I attended school in Connecticut and applied to the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy in Boston. Growing up in a bilingual environment and interested in history, I wanted to pursue a career in diplomacy. I was lucky enough to pass the Foreign Service exams. I was given a choice of five areas, but I suspected that as a gay man I would probably have problems in some sectors, more sensitive from a political and security point of view, so I chose the press and culture. My first foreign assignment was in Yugoslavia in 1983-84, and after a short break in Washington D.C. I was supposed to continue to South Africa. However, this break ended up lasting ten years. When I was preparing for my next mission in Cape Town, I was summoned to the internal affairs department. My nine-hour interrogation took place on August 21, 1984, a fateful date for me and our country. During the interrogation, I voluntarily admitted that I had been in closer contact with two local men in Yugoslavia, which they considered a violation of security regulations. The whole affair did not go well, and my assignment to South Africa was canceled. And after a long anabasis, I was told that I could no longer serve as a diplomat abroad, but only in a clerical position in the USA, because I was blackmailable due to my sexual orientation. I was not going to accept this decision and started to sue the Department of State.

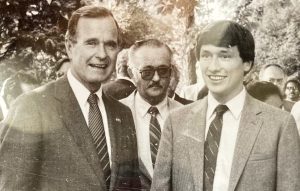

I was greatly helped by Frank Kameny, a well-known gay rights activist who was discharged from the U.S. military solely because of his homosexuality and fought for similarly persecuted people. He connected me with the non-profit organization American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), which “defends and preserves the rights and freedoms of individuals guaranteed to all persons in the country by the Constitution and the law.” When you decide to sue the federal government, you need good lawyers, and above all, a lot of money. Of course, I knew that I could not do it alone. Fortunately, the ACLU took an interest in my case and referred me to a prominent law firm. I was assigned two lawyers, and together we began the exhausting legal battle. I will never forget the first sentence of the other party’s lawyer in court. He said: “Mr. Krč is an open and notorious homosexual.” I found it so terrifying that in the 1980s in America, in the land of freedom, something like this could happen. Moreover, it was not true at all; at that time, I was still quite secretive about my orientation and few people knew about it, not even my parents. Many advised me not to engage in a futile struggle, to leave the Department of State and find a job at a university or law firm, where I would have peace, but my determination was firm. Moreover, based on the humiliating public exposure of my privacy, I decided to live differently. I moved to Dupont Circle, a well-known gay neighborhood in Washington, and also became a proud gay activist. After two years, my faith in justice paid off. A three-member judicial tribunal unanimously ruled that my dismissal from the foreign service was unjustified and ordered my superiors to call me back. But the Department appealed, and years of legal wrangling followed. For more than a decade, I worked for the International Visitor Leadership Program, which fell under the education division and provided trips to the USA and professional internships for people from abroad. Thanks to this assignment I had the opportunity, for example, to be present at Václav Havel’s legendary trip to Washington, D.C., in early 1990 and to interpret for several groups of Czechoslovak deputies, mayors, and journalists after the Velvet Revolution.

The election of President Bill Clinton also helped me a lot. His administration banned discrimination against gays in government departments

I complained to a senator about my superiors´ actions and the deliberate delay in sending me abroad, and I even gave an interview to the Washington Post. In the meantime, I also had to pass the polygraph examination twice and other unpleasant scheming. Eventually, I got back into the foreign service and at the same time, in 1992, I co-founded the organization GLIFAA (Gays & Lesbians in Foreign Affairs Agencies) within the Department of State. The election of President Bill Clinton also helped me a lot. His administration banned discrimination against gays in government departments which had been common practice up until then. Suddenly, everything turned for the better, and I was allowed to go abroad again. I had wonderful years ahead of me at embassies and consulates in Istanbul, Frankfurt, St. Petersburg, Budapest, Prague, where I served as spokesperson between 2002-2006, and then in Vienna. A very nice career and some satisfaction for previous inconveniences. It was also important to me that after my case, no one became a victim of career bullying just because of sexual orientation. Until 2018, I held various positions at the headquarters in D.C., and since then I have been enjoying retirement, living half in D.C. and half in Prague, in my beloved Vinohrady.