Fred Terna

I was born in Vienna in 1923, but my family lived moved to Prague when I was less than three years old. My childhood was happy until the German occupation. From then on, the life of the Jewish community of Prague, that of my family, and also mine was quite restricted and confined. My formal education came to an end early in 1939 at age fifteen. Levels of oppression were added from day to day. Food rations were reduced. We had to always wear a yellow star. There was a curfew at 8 o’clock. Several families were forced to move together into one apartment. Anything of value, radios, jewelry, bank accounts, art, were confiscated. Random brutality and terror accompanied each one of these steps, including even physical attacks against old people and children. Gradually the entire Jewish community was shipped to transit camps and from there to the death camps such as Auschwitz and Treblinka.

random brutality and terror accompanied each one of these steps, including even physical attacks against old people and children

On October 3, 1941, I was put into a labor camp named Lípa, in German called Linden bei Deutsch-Brod. Then from Linden in March 1943 I was moved to Ghetto Theresienstadt, from Theresienstadt in 1944 to Auschwitz, and from Auschwitz to a sub-camp of Dachau, Kaufering. Together with other prisoners, I was liberated by the Americans on April 27, 1945, after three years, six month, three weeks, and two days in concentration camps. I was one of the shuffling skeletons photographed by liberating allied soldiers. I weighed less than 35 kilos, about 75 lb., and I was near death.

My survival was due to luck. I was, statistically, of the right age, useful as slave labor, old enough to be picked for temporary enslavement, rather than to be sent immediately into the gas. When every tenth was shot, I was number nine. On a long train ride in a jammed cattle-car I did not die of thirst. On a long march my boots held out, and I was not shot lagging behind. I was emotionally well prepared by my father for the stress that was to come my way. I know that I owe my emotional survival to my father’s teaching. I was rather young then, but I always knew what I was, what my tradition stood for, and that my oppressors were doomed criminals.

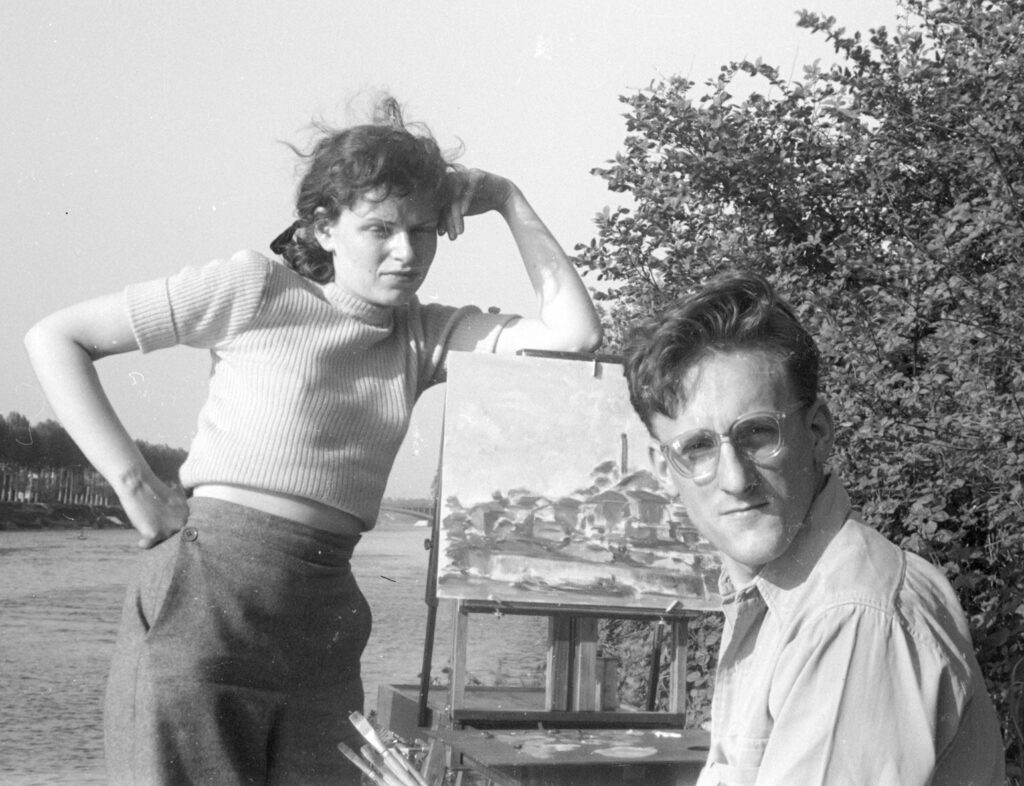

When the war came to an end, I was the only survivor in the Taussig/Terna family. I had to be hospitalized for a long time and finally returned to Prague as a repatriated Czechoslovak citizen. In 1946, I married Stella, my girlfriend before the war and at Terezín. When I was strong enough to work, I took a job in an office, and then in a film studio. After we realized, the Communists would take power in Czechoslovakia soon, we left for Paris. I started to work as bookkeeper for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee and informally studied at the Academie de la Grande Chaumière and the Academie Julien, where I was very much inspired by the work of the Cubists and post-Impressionists.

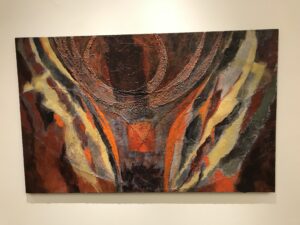

In 1951, we decided to move to New York. Enroute, we spent a year in Canada, first in Toronto and then in Montreal. We always knew though we wanted to live in New York. Stella had two uncles there. We were lucky again. I got a job quickly and found an apartment on West End Avenue at 101st Street. The building had converted some small servant rooms on the roof into tiny apartments, so we had had a nice penthouse apartment. Not a bad start for refugees who arrived with a few suitcases only. I fell into art completely. I elaborated on the prevailing modes of Abstract Expressionism. Using folded canvas, sand, and pebbles, I sought to activate the tactile senses, layering fields of depth, and creating visual tricks.

We always knew though we wanted to live in New York

Me and Stella got divorced sometime later. In 1982, I married Rebecca, and we raised Daniel together. I consider myself a happy person, with a wonderful wife and promising son, a community I am comfortable in and a job I like.

Fred Terna became internationally recognized as an artist and scholar. He has lectured extensively and exhibited his work in several solo and group shows. His work is included in a variety of private and public collections including the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., Albertina Collection in Vienna, and the Yad Vashem Museum in Israel. He has never forgotten about his Czech background and still speaks Czech fluently. Fred Terna died on December 9, 2022 in the age of 99 in New York.