Eva Jahoda

It was in 1951, when I was born in the former Czechoslovakia, in the most beautiful historical city of Písek. Mother was so glad she gave birth in May, there were so many flowers and sun everywhere. She could proudly take me out for walks with the stroller. My father was in the army and didn’t see me until a few months later. The family surname Hava comes from Turkish and it means air. Dad’s family originally came from Turkey, Serbia, Hungary and Slovakia, and after World War I finally settled in Písek. Mom and all her ancestors are from southern Bohemia. My sister was born when I was two years old and we all moved to Hradec Králové. Dad got a new job there at a hospital. He was a doctor and my mother worked as a pharmacist. I have beautiful memories of life in Hradec, we traveled a lot, went skiing and once even took a train to Bulgaria to the sea. In 1962, we moved to Prague because my dad left the army and was assignment to the hospital on Petřín hill. We lived in the Krč quarter and at the beginning, I hated it there because I lost all my friends. Eventually I got used to Prague; it seemed more fun and free. In addition, I met my lifelong friend Helena. We spent all possible time together and shared everything. We exchanged many letters over the years and finally met again in 1990. Since then, I have been visiting her and staying with her every time I visit the Czech Republic.

The family surname Hava comes from Turkish and it means air

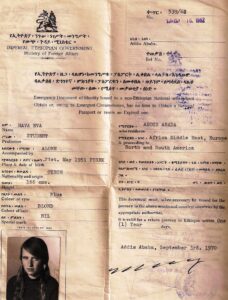

Once, there was an advertisement in a medical newspaper that they were looking for medical doctors to work in the Abyssinian Empire, today Ethiopia. Dad applied and was selected, along with about fifty others. In April 1965, we arrived to Addis Ababa, the capital of Abyssinia, where he got a job at the Menelik II Hospital. Also a number of Czechoslovak experts in industry, agriculture, education and healthcare were invited to Addis. At that time there was no Czech school, but the workers were allowed to bring their families. Every year the children had to come to Czechoslovakia for a couple of weeks and pass exams in Czech, Russian, Geography and History. This lasted until November 1968, when the Czechoslovak government recalled all staff, even from the embassy and trade department. However, only a few returned. Towards the end of 1970, Ethiopian student protests began and a political coup was imminent. The Czechoslovaks who remained were looking for a new refuge. Most of our people went to Canada, The Netherlands, Sweden, one family to Congo, another to Tanzania, and we ended up in Rhodesia, today Zimbabwe, in November 1970. It was a big shock to find ourselves in such a sleepy country, gripped by international sanctions.

There lived a few families who worked for the Bata shoe company in the town of Gwelo (now Gweru) and also a few former soldiers from Great Britain who did not return to Czechoslovakia after the war. I had just finished high school at the time. Like many others, we were stateless and unable to obtain passports. Even for visas to Rhodesia, we first had to wait in Rome for about three months. As soon as we arrived, dad had to leave to work in a hospital in a town about 200 kilometers away from Salisbury (today Harare). I stayed alone in the nuns’ home to train as a nurse. I felt very lonely. I made a lot of friends in Abyssinia over the years and got used to Amharic, Italian, Arabic, and suddenly everything was new again. However, I successfully completed my education with the title of registered nurse. I didn’t enjoy it there. All the girls were English or Afrikaner, too polite and unfriendly. It was difficult to communicate with them. The only exception was Elizabete, a Portuguese girl who had previously lived in Kenya and Mozambique. We are still friends, we often call each other and I visited her a few times in Canada, where she now lives.

After graduation, I married Josef, who was also Czech. He worked at The Paper Mill in Norton, so we settled there and had two sons. It was the late 1970s and the civil war was raging in Rhodesia. All white men were enlisted in the army away from home. Women had to learn to use weapons. Shooting was heard every night. I slept with my boys in a locked bedroom, barricaded and with two German shepherds guarding the lounge. I had the gun lying next to the bed. Back then, everyone had to carry a gun even when shopping. Almost every day we heard that someone we knew was killed. Our community of local white women lived together under a permanent stress, went to funerals, traveled in an armed convoy around Salisbury to do the shopping once a week, and most of all waited for our husbands to return safely from combat missions in the bush. Rhodesia was heading inexorably towards independence and one white family after another was leaving. We saw no future there for our children either. In July 1981, we emigrated to Australia, on Rhodesian passports and obtained entry visas as refugees. Dad opened a clinic in the town of Marandellas (today Marondera), where he died in 1983. My sister graduated as a librarian in England, got married and returned to Salisbury, where our mother lived with her and her husband.

I still feel that I don't quite belong in Australia, but I´m also not part of the Czech Republic anymore

Our family settled in Melbourne. The beginnings were easy thanks to the help of our friends. We already spoke English. Soon I got a job in a nursing home. Australian authorities recognized my training certificate as Rhodesia was still a member of the Commonwealth. Later, I also obtained a bachelor’s degree in health care and a management diploma and won the selection process for the director position in a care facility for the elderly. In my professional career, I had reached the peak. I especially enjoyed assisting the elderly – immigrants. I always liked to learn foreign languages, which helped me to understand different cultures, values, and religious beliefs. In 1989, the totalitarian regime ended in Czechoslovakia. This event actually means a lot in my life. In June 1990, after twenty-five long years, I visited my home. I saw many changes there, met relatives and friends. Now I try to visit the Czech Republic almost every year, usually for several months. I still feel that I don’t quite belong in Australia, but I´m also not part of the Czech Republic anymore.

Life is a continuous journey…

Shelter

I worked with Eva for more than 7 years at Villa O’Neill. She had very good public relations with everyone. I become so close with her cz she told me she lived in Rhidesia now Zimbabwe and she knew the language ie “shona”.I used to give her melie meal ie hupfu to cook sadza and green vegetables ie jomoriyo to eat sadza with.We used to meet with other staff twice or thrice a year for dinner .Eva is sadly missed.

Judith Anne Ibrahimoglu

That was the most beautiful story I ever heard . Dear Eva so sad you had to leave us .

Lou ann goldblatt

Eva was my distant cousin thru the Hava, dorman family. What a life she lived, so much movement and exposure to so many people and places. We connected on Facebook. She loved her friends, travel and of course her family. I send my love to them in her memory.

Lou ann goldblatt

Marge Wright

The World misses you