Miloš Pelikán

I was born in Prague on June 27, 1926. My father, a friend of T. G. Masaryk and General of the Health Service Rudolf Pelikán, was a hero of the Czechoslovak Legions in Siberia and the commander of the military hospital in Vladivostok. In 1920, he evacuated from Vladivostok aboard SS America and headed the medical unit on board ship which transported 6,000 people. After he returned back home, he received the Czechoslovak War Cross and other military awards. I had three sisters, Eva, Alena and Jitka. We went to Catholic school and lived in Dejvice, where my father’s friends, such as generals Jan Syrový and Rudolf Medek, often came to visit us. Sometimes my father also received an invitation to tea at Prague Castle from T. G. Masaryk, his close friend. I remember how the president shook hands with all of us children and talked to us. We usually spent our summer holidays in Vilémov in the Vysočina Mountains, where my mother’s parents, the Majvalds, owned a mill. During the First World War, they supplied flour to the locals and saved many people’s lives. It was a large farm with a garden, an orchard, horses, and forests around it. Later, they sold it and bought a house in Tábor, where we also spent holidays and I remember how I used to go fishing there with my father. His parents, both teachers, lived in the village of Maleč, also in the Vysočina. My mother Jana was a great cook and knew how to make potato dumplings in a hundred different ways. I learnt how to cook by watching my mother and helping her. We had a wonderful childhood.

I worked for the Department of Agriculture for some time but decided to leave the country

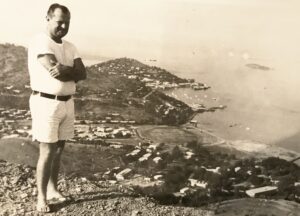

I was a teenager when I saw the German tanks rolling to Prague. It was also the first time I saw my father shed tears. Following the World War II, I was accepted to the Czech Technical University to study agriculture. However, due to political reasons, I could not finish my studies, and in general, conditions in the republic began to rapidly change for the worse. I worked for the Department of Agriculture for some time but decided to leave the country. After spending some time in the DP camps in Germany, I was accepted as a refugee by Australia in February 1950. The voyage on the ocean liner Fairsea from Bremerhaven took several weeks. I settled in Melbourne and worked on the wharves, for the Water Authority and the large construction firm Johns & Waygood Ltd. In 1962, the Department of Territories in Canberra advertised for the position of Assistant Inspector (Lands) in The Territory of Papua New Guinea at the Administration Headquarters, in Konedobu, Port Moresby. In those days, the second largest island in the world was divided into two parts. The western one belonged to Indonesia, while the administration of the eastern part was entrusted to Australia by the United Nations. I got the job and attended the compulsory training required for all personnel working in a Pacific permanent overseas mission. I was already married to Mary and our family had grown to include son Miloš and daughter Jana.

We moved to Port Moresby, which became our tropical home for fourteen long years. To be precise, I first left alone and the rest joined me a sometime later. There were many Czechs and Eastern Europeans who went to serve in PNG. We regularly got together for social occasions. It took a while to adjust to the tropical climate and the rigors of the bush which in many areas was not for the fainthearted. Even the news of the birth of my son in Melbourne reached me deep within the Papua New Guinean jungle. I was doing fieldwork together with a team of the local workers. We had ventured into the bush where there was no radio contact. All of a sudden, my colleagues stopped doing what they were doing and became silent. They were listening to the kundu drums echoing through the bush. They then looked at me and announced: „You have a son!” The news of the birth of my son came from Melbourne through to Port Moresby, then to the government station and from there all the way to me via the kundu drums.

I initially worked in the Land Development Section of Lands, Surveys & Mines and in my time, there was successful in securing many promotions within the department. My work and responsibilities over the years involved a sound knowledge of land ordinances, the interpretation, engineering-geological surveys and the creation of maps, land development proposals for agriculture and pastoral leases, land settlement and sub-divisional surveys, liaising with other government departments and many other responsibilities and tasks. I held senior positions within the administration which enabled me to have authority and decision-making capabilities on a daily basis. Early in my appointment I travelled throughout the island via foot, landrover, river canoes, helicopters, small planes…

Without the assistance of my trusted friend and colleague Madima Sedewa and his extensive local knowledge and interpretation capabilities, it would have been very difficult on these expeditions. Papua-New Guinea is truly the ‘land of the unexpected’ and fieldwork could be physically and mentally challenging.

In October 1973, I was appointed “Principal Land Development Officer”. It was one of the most important positions in the Australian administration. I think I did my job well because when the independence was approaching (Editor´s note: it happened on September 16, 1975 after a long preparation phase and transition of power), Michael Somare, a leading politician who soon became the first Prime Minister of Papua -New Guinea, sent me a personal letter and asked me to stay in office for another year. I finally ended my island mission in 1976 as the head of Land Settlement Division, Lands Surveys and Mines Department.

For me, the Velvet Revolution meant the possibility of visiting Czechoslovakia and later the Czech Republic on a regular basis and enjoying precious time together with my sisters

We returned to Australia and I retired, in my fifties. My wife and I bought a property on the Tweed River in New South Wales where I enjoyed fishing and gardening. In the mid-1980s, we settled in Melbourne. For me, the Velvet Revolution meant the possibility of visiting Czechoslovakia and later the Czech Republic on a regular basis and enjoying precious time together with my sisters and extended family, after such a long separation. I usually spent a few months in Europe every year. My wife Mary visited Prague as well, and we spent many happy times together visiting all the places of my youth, enjoying family gatherings, memories and celebrations. It was like a second honeymoon! Moreover, in 1991, with a delay of more than forty years, I finally received my university diploma.

Miloš Pelikán passed on June 15, 2024 in Melbourne in the age of (almost) 98. Only three months earlier, we had the pleasure to meet at the Honorary Consulate of the Czech Republic in the Domov gallery, next to the Sokol Hall.